© ROOT-NATION.com - Use of content is permitted with a backlink.

The world of chips and semiconductors has long been engaged in a major war for technological dominance, with the main struggle taking place between Taiwan, the US and China.

The semiconductor crisis of recent years in the global economy has led to a rise in the price of chips and caused problems in the automotive, gaming and medical industries. Why is this happening? Is it just about economic issues? Or is it all about big politics? Many experts and journalists are asking themselves these questions.

Read also: Все про специфікації USB та чим USB Type-C відрізняється від USB Type-A

The dream of the chip giant TCMS

The headquarters of the Taiwanese chip giant TCMS welcomes us with a big red sign that reads “Dream”. It is the dream of capturing a major position in the semiconductor market that is driving the global clash. This is the first conflict centred on non-defence technologies. Whoever has the semiconductors will rule the world.

The journey from Taipei to Hsinchu takes just over an hour. There is nothing particularly interesting in this small city: neither valuable monuments nor beautiful architecture. Even its location on the coast of Taiwan Bay does not guarantee breathtaking views. And yet, from the capital of Taiwan to this city of just over 400,000 inhabitants, a stream of cars carrying thousands of engineers, programmers and cybersecurity specialists flows along the motorways every day.

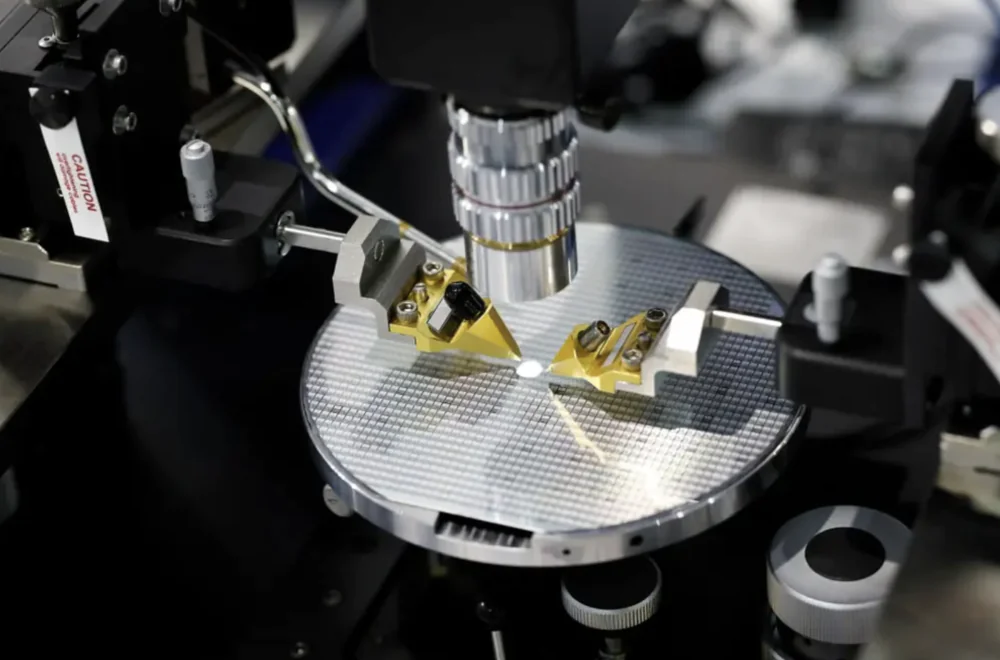

Hsinchu needs a veritable army of such workers. This is not surprising, as the more than 700 hectares of industrial park that was created here more than four decades ago now hosts as many as 360 technology companies, large and small. The technological jewel in the crown of all of Taiwan is the area of the Taiwan Semiconductors Manufacturer Company, better known as TSMC. The area looks extremely calm. There is nothing like the pubs, shops and neon atmosphere of Taipei.

But don’t let this calmness fool you. It is enough to stop for a moment near the inscription “Mriya”, and in a moment of dreaming, the building or the surrounding area is quickly stopped by the guards who meet curious tourists. The entire territory is carefully monitored by thermal imagers that detect any movement and quickly alert you to unexpected guests.

And no wonder: TSMC is not only the technological pride of Taiwan. First of all, today it is a guarantor of the security of the entire state. After all, this is a country that is likely to become the source of another war. Although few politicians and experts believe in the scenario of a military attack by China on the Republic of China (as Taiwan is officially called), the island is already at the centre of the war.

As you can imagine, this is a war for dominance over the semiconductor industry.

Read also: Everything you need to know about Microsoft’s Copilot

Turbulent times on the chip front

When a video report appeared on 6 December showing US President Joe Biden standing side by side with TSMC CEO Morris Chang announcing the Taiwanese company’s large-scale investment in Arizona, it became clear that this was not all. It was not that Chang announced a huge increase in investment from the planned $12 billion to $40 billion. The key was the agreement that one of the most modern semiconductor manufacturing plants in the world was to be built in Arizona.

And on 8 December, it was reported that the Dutch government plans to impose strict restrictions on the export of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment. It is in the Netherlands that ASML, a tycoon in the production of machines for printing chips in 14 nm or lower (i.e. more advanced) lithography, operates. These machines should now be banned from being sold to China. This will not be an easy decision, as sales to China accounted for 15% of ASML’s revenues last year. However, there are many signs that the government in Amsterdam has already taken up this area.

On 9 December, Japan’s Industry Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura received a phone call from Gina Raimondo, the US Secretary of Commerce. She strongly encouraged Tokyo to join the chip industry, not only to start working together on their production, but, above all, to help cut off China from the supply of semiconductor technologies. Although there is no official response from Japan to this proposal yet, the fact that the Japanese company Rapidus is signing a contract with the American IBM for the production of 2-nanometre chips speaks volumes.

China’s reaction was almost immediate. On 12 December, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce filed a complaint against the United States with the World Trade Organization. The reason: The United States is about to cause a global crisis with its policy of restricting Chinese chip manufacturing plans.

All these events in just a few days in December show how hot the atmosphere is around the seemingly boring chips, or rather their production. In reality, however, these tumultuous emotions have been brewing for a long time.

Last year’s visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, showed how strong they are. While she was on her way there, the political situation on the island was so heated that many experts and analysts were, to put it mildly, puzzled by the implications of the visit. Why start another global conflict when the world is shaken by the war in Ukraine? Why are Pelosi and the US teasing China?

Today, it is clear that the US had a specific goal, and the meeting between Pelosi and Morris Chang was not accidental. This goal is to limit China’s production capacity (by cooperating with Taiwan and convincing Western countries to cooperate) and thus cut off China from chip production.

Like oil and gold

Chips are everywhere today. The laptop I’m writing this on won’t even turn on without them, let alone connect to the Internet and store data. Without chips, there would be no huge data centres, no smartphones, no refrigerators, no washing machines, no vacuum cleaners, no e-scooters, no cars.

This is what all strategists in Beijing and Washington understand. Because all advanced technologies – from machine learning to missile defence, from autonomous vehicles to military drones – require advanced chips.

Today, there is not a single important area of life that could function without semiconductors. This includes not only industry, IT or the military, but also, for example, modern medicine. Our overall well-being and prosperity depend on access to them. A drone alone contains from 1,500 to 3,000 microprocessors. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), the global value of this market is expected to exceed $600 billion this year. In 2022, it reached $553 billion, and a year earlier – $440 billion. Consulting firm McKinsey estimates that global demand for semiconductors will only grow, and by the end of the decade, the industry is expected to be worth $1 trillion.

It is no surprise that today chips are worth their weight in gold and oil. The pandemic showed how valuable this commodity is, when the disruption of the chip supply chain led to a shortage of chips and affected the global economy. There were thousands of cars on the assembly lines that could not be sold because they could not even open the doors without chips. Other mobile equipment manufacturers began to run out of products to sell. It was then that the world realised the truly enormous importance of chips.

However, there is no industry in the world that is more geographically concentrated than chip manufacturing. Even crude oil production is more evenly distributed. Saudi Arabia is a tycoon, but it is responsible for only 15% of global production.

As for chips, we have several global monopolies. Taiwan is the undisputed leader in semiconductor production. The Netherlands, with ASML and an enthusiastic machine market, controls advanced lithography. South Korea produces about 40% of memory systems. And the US is still the main developer of know-how and data for printing on chips.

In this scenario, China, which is considered a technological power with ambitions to become the world’s No. 1 power, is becoming dependent on the rest of the world. China still exports almost all the semiconductors it needs. And their plans to create their own semiconductor industry have been confronted by the US counterplan to cut China off from all the technologies needed to create truly modern chips.

And at the centre of this plan is an island in the Pacific Ocean, around which more and more unresolved problems are accumulating. On the one hand, chips are a guarantee of the country’s security, and on the other hand, they are the reason for China’s even stronger desire to annex Taiwan.

Read also: Windows 11 22H2 Moment 3 update: what to expect?

Taiwan risks

According to the Boston Consulting Group, in 2021, 90% of the most technologically advanced semiconductors came from Taiwan, mainly from TSMC. Half of the company’s revenue comes from the US market, and about 10% from the Chinese market. Taiwan has a big advantage over its competitors both in terms of production volume and quality. Their processors are made using 5 nanometre technology. This means they are the most efficient and energy-efficient on the market. According to the report, in 2025, TSMC will be able to produce a processor using 3nm technology, which will allow a smartphone to run for about 4 days on a single charge. All in all, this business contributes as much as 15% of Taiwan’s national GDP.

But Taiwan has been in a geopolitical rift for decades. The country’s international position can best be described by the enigmatic phrase “it’s complicated”. Officially, as the Republic of China, Taiwan considers itself the political and institutional heir to pre-revolutionary China, and the PRC as the usurper. For the PRC, however, Taiwan is a “rebel province”, and as part of its one-state policy, Beijing effectively fights all international signs of recognition of Taiwan’s statehood. As a result, only 16 countries officially recognise Taiwan as an independent Chinese state. The situation is further complicated by the fact that not all Taiwanese politicians and not all Taiwanese people recognise that this is the “real China”. On the contrary, the perception of Taiwanese statehood is strengthening.

In such a situation, reinforced by constant threats from Beijing, semiconductor potential has become Taipei’s main bargaining chip in the global political puzzle. There is not a single Taiwanese politician who does not have his or her own views on semiconductors and the Taiwanese government in this area. All that’s missing is a funny mascot that pretends to be a chip and is sold as magnets, key chains, and figurines. But even without that, the role of semiconductors in this country’s prosperity and security is crucial.

“We produce about 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors. Moreover, 40% of their exports are shipped by sea. Therefore, if any conflict erupts around Taiwan, it will be a disaster for the global economy. And we would not want to see that happen. Therefore, it is our duty to ensure that there is no conflict between Taiwan and China,” says Joseph Wu, Taiwan’s Minister for Foreign Affairs.

“This is an unprecedented situation. The guarantor, let’s face it, of the survival of the entire state is technology, and not defence technology at all. So why did Taiwan, as if putting its head under the axe, agree to move part of its production to the United States?

The Taipei government itself is probably not so sure of the firmness of its position. In early December 2022, the local Ministry of the Interior announced the introduction of strict restrictions for technical workers in key sectors who wish to travel to China. And not only for those travelling for work, but also for those going on a trip or just wanting to drive through China. Technical employees of government-sponsored companies (and this includes semiconductors) will have to obtain a special permit from the National Immigration Office 60 days before their planned departure. Moreover, it is expected that the new rules will remain in force for another three years after the person stops working for such a technology company.

And this is only the first step towards protecting this most valuable asset. Taiwan will train a special team to protect TSMC’s technology and trade secrets. Also from the Americans. Thus, despite the increased investment in Arizona, the equipment to be produced there is at least one generation weaker than that produced by the parent company in Taiwan.

But will the United States agree to such a deal?

Read also: 7 coolest ways to use ChatGPT

Chips “made in USA”

Under the influence of the semiconductor crisis and China’s claims over Taiwan, the Biden administration has clearly gone on the offensive. It’s one thing to invest in your own market, it’s another to close ranks against China.

In mid-October, shortly before the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the US issued a presidential decree that imposed additional restrictions on the export of advanced semiconductors with transistor sizes below 14-16 nanometres to China. That is, on the chips that are most in demand on the market. Importantly, this applies to both those made in the US and those developed by US companies but manufactured in third countries. The dessert was a ban on American citizens supporting the Chinese chip industry without special licences. In effect, an ultimatum was given: either an American passport or work for Chinese companies in the chip sector. The reaction was immediate: most managers and engineers began to leave their jobs with Chinese companies in droves.

In addition, the United States is trying to engage its allies in cooperation. Hence the calls to Tokyo and plans for the Netherlands. Anything to cut off China from the latest technologies with a real wall. But this does not mean that the US will completely get rid of its dependence on semiconductor imports. Bloomberg’s Tim Culpan wrote in his commentary immediately after the investment in the Arizona fab was announced with fanfare: “Sorry, US, but $40bn won’t buy you chip sovereignty.” It may not buy sovereignty for the whole country, but Apple, whose CEO Tim Cook accompanied Biden and Morris Chang, may start to feel more secure and independent. After all, a quarter of Taiwan’s most advanced semiconductors go to Cook’s company.

The technology will remain more or less in the hands of the Taiwanese. However, in the event of any security problems on the island itself, the United States will have support. It remains extremely important for the United States that China does not have such support.

Read also: What is CorePC – All about the new project from Microsoft

But China is in the game

Currently, China produces only about 15-16% of microprocessors used by its own companies. The rest is imported. China wants to change the situation as soon as possible and increase its own production to 70% by 2030. To achieve this, Beijing is spending huge amounts of money. Tax rebates, research and development subsidies, support for importing components and even buying foreign competitors are also a huge help for companies that want to enter the chip industry.

In total, Beijing has so far allocated more than $150 billion to stimulate progress in the semiconductor industry. Obviously, this was not enough, but Reuters reported that China is working on an additional support package worth more than 1 trillion yuan ($143 billion) for its semiconductor industry. This clearly shows the importance they place on this industry.

In June, Xi Jinping visited a semiconductor company in Wuhan. He decided to personally inspect China’s important semiconductor manufacturing facilities.

“We must take the life of technology into our own hands. If every city, every high-tech development sector, every technology company and every scientist can follow the government’s guidance on technological innovation, we can certainly achieve the goals,” Xi Jinping said.

The goals he was talking about are much more important than the production results at one factory. Although it is the semiconductor fabs that are crucial. After all, four years earlier in Wuhan, at a semiconductor factory, Xi had waxed poetic in explaining that semiconductors are as important to industry as the heart is to the human body.

The situation with sanctions against some Chinese companies has shown that something has to be done. All companies, not only from the US but also those operating in this market, were banned from selling semiconductor technology to Huawei. It was a cold shower because it showed that China’s most important technology company could be brought to its knees. It is precisely because of the lack of chip manufacturing technology that there was such a shortage of Huawei flagships on store shelves. Huawei has almost lost its position in the global smartphone market. The company has not yet recovered.

No wonder China wants independence. However, plans are plans, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to implement them. Even a lot of money invested in this industry does not always help. The most striking example is the efforts of Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. from Wuhan. The same company that Xi Jinping visited. It spent a staggering $20 billion on investments in chip manufacturing. Everything was funded by a government subvention. The company promised that in return, in 2020, it would supply 30,000 modern semiconductors with a size of 14 and 7 nanometres. However, the plans collapsed even before the plant produced a single chip.

However, there are also first successes in China. This summer, it was reported that SMIC, one of China’s largest chipmakers, had produced a 7nm chip, only one or two generations behind the industry leaders.

This explains the American offensive on the production and acquisition of cutting-edge chips and microchips, which suddenly erupted against the backdrop of the US-China confrontation. And the chip war goes some way to explaining the words of Morris Chang, who declared in his speech in Arizona that “globalisation and free trade are almost dead”.

In fact, one can only dream of free trade during a conflict. But for some reason, I am sure that we will see a very interesting confrontation between China and the US. Perhaps it is this confrontation that will drive progress in the semiconductor industry.

Read also:

- Bluesky phenomenon: what is the service and how long will it last?

- What are 6G networks and why are they needed?