© ROOT-NATION.com - Use of content is permitted with a backlink.

Today, let’s discuss techno-feudalism as a new global order—because it feels appropriate to say, “Capitalism is dead; long live techno-feudalism.”

This idea suggests that capitalism is not disappearing but rather shifting into a new phase—one characterized by increased concentration of power and control. Instead of traditional market competition, we are seeing the rise of monopolistic digital platforms that function more like feudal estates, where users and workers are increasingly dependent on a few dominant corporations. If capitalism is reaching its limit, this shift toward techno-feudalism may define what comes next.

Like a serf bound to the keyboard, I spend eight to ten hours a day typing—working, entertaining myself, stressing, or simply sitting. I write, edit, respond to emails, and occasionally join online meetings. This is my job, and I get paid for it. But there’s another kind of work—done before, after, or even during my primary job—for which I receive nothing. Aside from sleep, the last true moment of freedom, my time and effort generate profit for Musk, Zuckerberg, and the rest of the so-called techno-feudal elite.

The new technological aristocracy—or more precisely, the cloudocracy (a term we’ll explore later)—benefits from the fact that a significant portion of modern journalism, along with many other professions, is now tied to an online presence. Unlike the few colleagues who have managed to escape this cycle of digital engagement and social media, I believe that for a journalist, visibility on the internet is not just beneficial but necessary.

Read also: All About Microsoft’s Majorana 1 Quantum Processor: Breakthrough or Evolution?

What is techno-feudalism?

However, I am not the only one working for free. Everyone reading this text, simply by being connected to the internet, becomes part of a vast, unpaid, and extremely cheap labor force fueling the new economic system—techno-feudalism.

Simply put, techno-feudalism is the process by which large technology companies absorb many functions that were once governed by market principles under capitalism. Just as capitalism emerged from the crisis of the feudal system, we are now witnessing a reversal of that transformation. Feudal-like relationships are increasingly replacing traditional market dynamics.

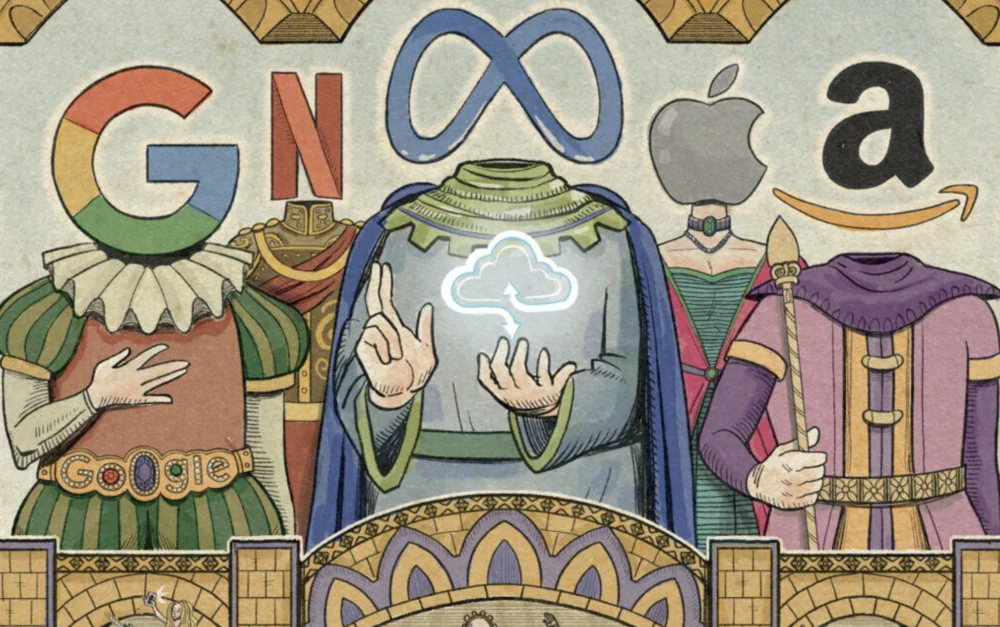

The concept of techno-feudalism was explored by Greek economist and politician Yanis Varoufakis in 2021. However, the term itself originates from French Marxist thinkers, particularly Cédric Durand, the author of Techno-féodalisme. Critique de l’économie numérique.

Read also: Tectonic Shifts in AI: Is Microsoft Betting on DeepSeek?

Digital stories for the poor

In his book Techno-Feudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Varoufakis argues that value creation is increasingly detaching from traditional markets, while technological oligopolies generate massive profits from new, digital sources. He traces the origins of techno-feudalism back to the 2008 financial crisis when large-scale money printing by central banks and severe cuts to public spending undermined capitalism’s foundations. At the same time, these policies fueled the rise of tech giants. This shift was further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, the artificial intelligence revolution.

In the new Theatrum Mundi, the roles have already been assigned. The kings and princes of this emerging system—Musk, Zuckerberg, Pichai, and others—are the cloud lords, the owners of “capital in the cloud.” Below them are a handful of masters and suppliers—small and medium-sized businesses, startups—whose survival depends on the whims and greed of these cloud rulers. App developers and small entrepreneurs must pay a form of tribute for access to their customers, much like medieval artisans once paid feudal lords for the right to trade on their lands.

Finally, there is the vast class of consumer-producers—the peasants of the 21st century, an era defined by data and artificial intelligence. Our photos, videos, posts, and even location data are processed by algorithms that convert them into a continuous stream of revenue for platform owners. These modern landlords no longer need to invest in traditional ways—building factories, hiring workers, or selling physical products to generate profit. Instead, they thrive on the wealth created by both ordinary users and businesses, who fuel the system simply by existing within it.

One might argue that the free market still exists, that corporations continue to operate, and that goods and services continue to flow—so what if a handful of tech giants dominate to the point of imposing conditions that resemble feudalism? To function within this system, you must pay for access to their domains. If you’re selling a mobile app, for example, you have little choice but to use Apple’s or Google’s stores—or find alternative ways to compensate for your digital serfdom (leveraging social media, the Google ecosystem, or platforms like OpenAI).

Under feudalism, peasants worked the lord’s land, producing goods and generating surplus wealth that benefited the ruling class. However, the lords themselves remained detached from the process. Now, consider Facebook: we create content, cultivate digital narratives, and generate surplus value—but it is the platform that profits. Occasionally, we might receive dividends, but only if we play by the platform’s rules.

Both medieval and digital overlords ensure that their subjects do not disrupt the existing power structure. You cannot simply take your content and leave Facebook, and any protests against these conditions are largely ineffective. The copyright protest chains that spread across Facebook in 2017 are a prime example. Did Mark Zuckerberg acknowledge them? In a way—by asserting full control over the content, leaving creators with no real leverage.

Read also: Most Fascinating Robotics Innovations of 2024

Is techno-feudalism capitalism on steroids?

Capitalism is fundamentally driven by profit—the difference between what is earned in the market and the costs incurred. Capital is invested in production, and once products are sold, revenue covers expenses, generating profit. This profit is then reinvested, leading to continuous capital accumulation—the core mechanism of capitalism. Techno-feudalism, however, operates on a different principle: digital rent. Instead of focusing on profit derived from production and trade, the dominant players extract wealth through control over digital platforms, data, and access. The emphasis shifts from capital growth to the ability to charge for participation in the digital economy itself.

The new rentiers are the major digital platforms that are reshaping the world. However, this emerging system is built on old, feudal principles. The traditional concept of a free market is gradually disappearing, replaced by a landscape dominated by closed platforms.

Powerful tech companies like Amazon, Google, and Meta today hold more influence than many countries. And they have set the terms.

These large tech firms succeeded by being the first to bet on a new “raw material”—our time and attention. In an era of depleting natural resources and growing political crises, this has become one of the last areas of potential expansion.

Suppose you have a business. Want people to talk about it? You need to be part of the social media ecosystem. Or maybe you’ve created an app, but to reach your audience, you have to use platforms like Google Play or the Apple Store. And these companies charge rent for access. You could choose not to pay, but that means no access to your audience. The only way out of the system is bankruptcy.

The system of dependencies is deeply entrenched. Being off the network is a luxury reserved for the wealthy, while for most, it’s an unimaginable scenario.

The trap set by large tech companies lies in the fact that, instead of demanding money like other businesses, they “simply” collect our data and attention. And this is very difficult to assess until you lose access to them.

When we started to realize that this deal was unfair, because the costs on our side outweighed the benefits, the gravitational pull of social networks had already formed. FOMO (the obsessive fear of missing out on an interesting event or opportunity) was compounded by behavioral addiction. This is why, in large tech service networks, we are not customers, but users—digital biomass. A customer comes and goes, fulfilling their needs and disappearing. A user, however, is hooked up to a “dopamine drip” 24/7 in exchange for the ability to track and manipulate their attention.

Every time we upload a video to TikTok, Facebook, or Instagram, we contribute to the capital of large companies. In this sense, we are modern “subjects” of those who generate capital. This is a historical phenomenon.

Read also: How Do I Build a Payment Gateway? 101 Guide for Beginners

Is it really back to the Middle Ages?

“We say, ‘This is a return to the Middle Ages!’ when someone tries to impose ignorance and superstition on us. Yet, modern technologies require development. We intuitively assume that the advancement of technology and artificial intelligence systems is a leap into the future. But what if techno-feudalism is a harbinger of civilizational trends that are characteristic of the past, rather than the 21st century?

The new Middle Ages doesn’t come with fire and sword. We almost voluntarily submit to it. We willingly accept its rules. The feudalization of capitalism is just one of the seven ‘new medieval’ megatrends currently shaping our civilization.”

These trends resemble macrostructures and processes more commonly associated with the Middle Ages than with the era of modern society. In addition to the economic trend, namely feudalization, there is also the political level, which involves the fragmentation and “networked” nature of political power, with multiple and overlapping centers of influence and authority.

The third trend is the demographic level, associated with a great migration of peoples, comparable to the movements seen at the end of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages. The fourth trend is the ethnoreligious level, marked by the return of religion to public discourse. The fifth trend refers to legal pluralism, resulting from the formation of a civilizational and religious mix. The sixth trend, the social level, signals a retreat from rationalism toward intuition, post-literacy, the absorption of digital soft emotions, and isolation from those who think differently. All of this is reflected even in urban planning, which represents the seventh level of the “new Middle Ages.”

In the Middle Ages, information was scarce. Few people could read, and there were no mass media outlets. Instead, there were bards, innkeepers, and heralds who conveyed the will of the nobility. Today, we face a situation where so much information is available that it’s almost impossible to determine which sources to focus on or trust. It’s enough to say that a large portion of this content is misinformation.

Thus, from the overload of information, misinformation arises: the informational capacity of the human brain becomes overwhelmed, leading to confusion.

From this, it’s only a step to a new illiteracy – the lack of skills or a conscious refusal to absorb information about the world. A person with too much information becomes indistinguishable from one who has no information at all. The situation is further complicated by social media, which create informational bubbles around people – virtual worlds of seemingly coherent information that are often a distorted fragment of reality.

Read also: End-to-End Encryption: What It Is and How It Works

New God and new elites

The Middle Ages were a time of religious flourishing. Today, for many, religion, and perhaps even God, is represented by technology and artificial intelligence. This marks a new starting point for the person of the new Middle Ages. Princes are anointed to the throne, while the peasants are forced to bow before it.

Only God matters, and even if a person is a creator, they exist solely to worship God.

In the Middle Ages, little attention was paid to the authors of works; various sects or other identity groups lived their lives according to scenarios close to their hearts. Today, social networks can trap us in bubbles to the point where we don’t even reject those who think differently—we simply ignore them. As long as there isn’t a global war, people with full stomachs in the AI era will be able to detach themselves from established identities and create their own. Whether those identities are imagined or not, it won’t matter.

Artificial intelligence, the Holy Grail of the new Middle Ages, will not only keep the masses under control but also further consolidate power in the hands of the elites.

We are already witnessing how artificial intelligence amplifies the advantages of the wealthy. In earlier times, figures like Croesus were, to some extent, dependent on creative individuals. Even with vast wealth, they still needed artists, writers, and craftsmen to bring their visions to life. Today, that dependency is fading. The rich no longer need skilled artisans, scientists, or artists—AI has absorbed their talents, often without compensation, and can now generate creative works at no cost. This suggests that the fundamental purpose of artificial intelligence is not just to expand access to creative capabilities for the elite, but also to sever the link between skilled individuals and economic opportunity.

The conflict between the new and old elites is starkly visible in Trump’s “dream country.” Traditional figures—journalists, lawyers, scientists, and bureaucrats—are being replaced by influencers and tech experts, the Red Guards of this new world. These “Bolsheviks” of the digital revolution despise the old order and seek to dismantle it. They believe in the existence of a deep state—a hidden, entrenched power structure that must be overthrown. But in their vision, it is not democracy or transparency that replaces it, but a new deep state, one where laws are dictated not by institutions or tradition but by the raw force of algorithms.

Startups and small businesses continue to believe in the old dream—that hard work and persistence will help them break into the top. But in the era of techno-feudalism, this path no longer leads to the elite; it merely secures a role in the support system.

There is no seat at the table for smaller players in the world of tech giants. Industry leaders may welcome entertainers—podcasters, influencers, and celebrities—but not real competition. Today’s startup founders can only dream of following in the footsteps of Gates or Jobs. Major corporations ensure that emerging players never grow large enough to become a threat.

Read also: 10 Examples of the Strangest Uses of AI

Report from the end of the world

The United States today serves as a testing ground for a world that may soon become reality.

Across the ocean, the old order is breaking down. The new “First Lady” of the U.S., Elon Musk, is using AI-driven algorithms to streamline and downsize government operations, replacing representative democracy with what is essentially Twitter-driven governance.

With the rise of the Trump-Musk alliance, the shift from capitalism to techno-feudalism has accelerated. This transformation is unfolding in real time—fast, unfiltered, and broadcast live for all to see.

Musk has a vested interest in keeping tech corporations as deregulated and lightly taxed as possible. In his role within the Trump administration, he is likely to prioritize policies that benefit his own companies while also advancing the interests of the broader tech industry.

I wonder how many American voters realized that supporting Trump would mean, for example, the removal of Lina Khan from the Federal Trade Commission or the end of the government’s aggressive antitrust approach. This wasn’t a major talking point during the campaign—regulation of big tech was rarely discussed at all.

Musk has encouraged his followers to evaluate scientific research—often on topics they may not understand. In practice, this means that individuals with no background in physics, chemistry, or biology are being asked to judge the validity of complex studies. But what criteria can someone use if they lack even a basic understanding of the subject?

Even the titles of research papers could become a target. If something “sounds strange,” it might be dismissed outright. After all, what significance could there be in studying mold or developing a third method of organic catalysis—when two already exist? (For reference, Benjamin List and David MacMillan won the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on the second method.)

It’s important to understand that this madness is not driven by power but by money. Mentally, Musk is primarily an entrepreneur. He knows that involvement in politics is a pathway to lucrative contracts and new markets. President Trump, who shares a similar mentality, is the perfect business partner. And while this may seem like good news, it doesn’t mean that things will be any easier.

Read also: Use It or Lose It: How AI is Changing Human Thinking

Escape from freedom

In the 21st century, most of us need digital tools not only to live well but simply to survive: smartphones, search engines, websites, and many other things. Without them, we wouldn’t exist. You could disconnect from online tools and use an old Nokia phone that doesn’t track you or scan your psyche with algorithms, but if you do, you’ll end up starving like a mercenary. So, I’m sorry, but you have no alternative.

We are mercenaries – we don’t have land or farms that generate income, but we perform freelance work as journalists, analysts, and managers in digital fields of the internet. Without the space of the internet, the web wouldn’t exist, and it wouldn’t generate any income. The internet and the digital world are the spaces of human existence. It’s important to understand that the old order is disappearing.

This is what brings intellectuals from Europe and the U.S. to despair. They feel a sense of powerlessness similar to what the elites of Ancient Rome once felt.

In the past, they tried to regulate the dynamics of the cultural-political melting pot of Europe during the Renaissance, but without any understanding of the dreams and beliefs of the divided communities. Seneca’s successors wrote treatises on equality, tolerance, and the need for harmony, while politicians wondered how to organize the angry mobs to prevent uprisings. It was a very modern dilemma: if the people do not dream of the tolerance offered by the elite, what language should they speak with them?

People who once considered themselves middle class are starting to live like the working class, and something inside them is breaking. Uncertainty is rising, selfish turns appear, and dreams of a strong leader emerge. This refers to the situation where people believe the most reliable way to protect their wallets, savings, and wealth in times of heightened economic uncertainty is to immediately stop financial aid to other groups. And who is strong today? The one who has money.

This mindset leads us straight into the arms of technofeudalism. Perhaps it’s better to live on a guaranteed basic income, eating the scraps left by big tech? After all, the need for order and existential survival becomes more important than freedom in its maximalist, left-liberal sense.

Read also: Panama Canal: History of Its Construction and Basis of U.S. Claims

New hope

The images of our imagination have been shaped by the constant surveillance and omnipotence of “universal corporations” that serve the entire lives of citizen-customers, as reflected in the works of authors like Lem, Dick, Huxley, Orwell, and Stevenson. However, in reality, people still possess a great deal of subjectivity. They do not live solely in the digital environment, and producers still have much to say to governments.

Recently, there has been much discussion about economists being beginner philosophers and the economy being a state of mind. Varoufakis’ techno-feudalism is exactly such a meaningful narrative. The problem with these narratives is that the more captivating and convincing they are, the worse it is for the facts that don’t fit them. Apologists of techno-feudalism overlook the role of democratic and oversight processes happening around social media platforms, as well as the very real struggle for information verification.

Politicians, mainly European, are trying to fight for sovereignty. The most commonly mentioned idea is a digital tax. Another one is a digital identity that belongs to the state, not issued by corporations. Another element discussed by both Varoufakis and the experts mentioned in this text is compatibility, meaning the ability to move freely between programs and systems. In practice, this means transitioning from Platform A to Platform B with all digital outputs (content we’ve created and our subscribers).

Forcing big tech to take such actions is difficult, but only countries, including those organized in the form of the European Union, and not individual users, can attempt to exert pressure. This is why techno-feudalists, like Musk and others in this world, fight against state institutions and supranational organizations. Hence, the White House’s aversion to the UN, NATO, the EU, and so on.

Contrary to appearances, not all regions will face a scenario like the one in Cyberpunk 2077, where powerful industrial and digital companies prey on a weak state. The world of two speeds (and two internets) is full of inequality. The question is, what will be better—to be a citizen of a developed center run by artificial intelligence, or of the periphery? Or perhaps there is a possibility of existing on an island outside the power of the big tech market, where the techno-feudalism of new kings will not be as strong?

If the new barbarians arrive on Tesla, will we be able to protect ourselves? This will only happen when we acknowledge that technology and technocracy are not neutral, because behind them are always people.

Jacques Ellul, a French historian, Protestant theologian, and sociologist, argued that “the intrusion of technology desacralizes the world in which humans live.” He emphasized that “there is no holiness, no mystery, and no taboos when it comes to technology. The reason for this is autonomy. Technology recognizes no rules or norms outside of itself.”

If the new Middle Ages are not destined to be a dark age, our norms and human principles could become the light for a new Renaissance.

Read also:

- Are Noise-Canceling Headphones Harmful? Insights from Audiologists

- Space Travel at the Speed of Light: When Will It Become a Reality?