© ROOT-NATION.com - Use of content is permitted with a backlink.

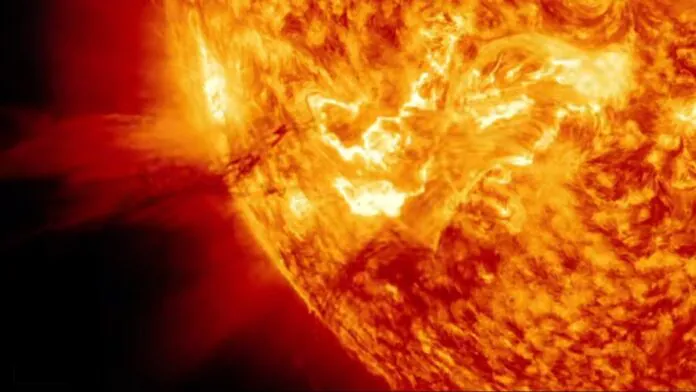

A powerful eruption, known as coronal mass ejection (CME), was observed from the other side of the Sun on the evening of April 11, and it took less than a day to fall on the Mercury – the planet closest to our star.

A giant plasma wave crashed into Mercury on Tuesday, April 12. On planets with strong magnetic fields, such as Earth, CME’s are absorbed and cause powerful geomagnetic storms. During these storms, the Earth’s magnetic field is slightly compressed by waves of high-energy particles that permeate the magnetic field lines nearby. These particles excite molecules in the atmosphere, releasing energy in the form of glow, creating colourful auroras in the night sky.

The motion of these charged particles can induce magnetic fields powerful enough to disable satellites as well as the Internet. However, unlike Earth, Mercury does not have a strong magnetic field. This fact, combined with its close proximity to our star’s plasma emissions, means that it has long been devoid of any permanent atmosphere. But the solar wind is a constant flow of charged particles, nuclei of elements such as helium, carbon, nitrogen, neon and magnesium. They, in fact, create a thin layer of atmosphere on Mercury. And this layer holds until the next release of plasma, which knocks out all that the planet has accumulated. As a result, the planet is followed by a comet-like tail of elements knocked out of the atmosphere and surface.

You can also help Ukraine fight with Russian occupants via Savelife or via an official page of the National Bank of Ukraine.

Read also:

- NASA’s new telescope will look for extraterrestrial organics

- Gamma-ray telescopes to help scientists catch more gravitational waves