© ROOT-NATION.com - Use of content is permitted with a backlink.

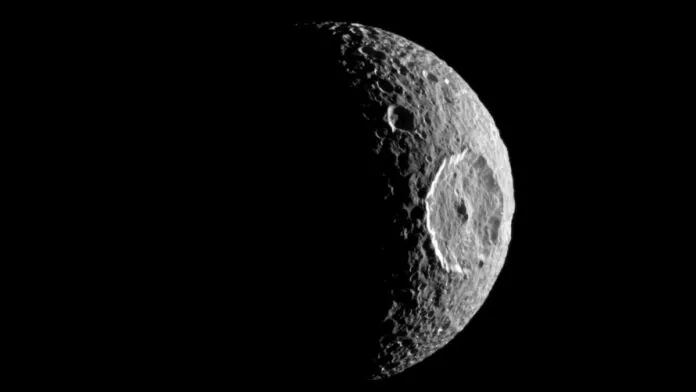

Hydrogen and oxygen ions emanating from the Earth’s upper atmosphere and settling on the Moon may be the sources of known lunar water and ice, according to a new study by scientists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. The work, led by Gunther Kletetschka, an associate research professor at the UAF Geophysical Institute, complements the growing body of research on water at the moon’s north and south poles.

The search for water is the key to NASA’s Artemis project, a planned long-term human presence on the moon. NASA plans to send people to the moon this decade. “As NASA’s Artemis team plans to build a base camp on the moon’s south pole, the water ions that originated many eons ago on Earth can be used in the astronauts’ life support system,” Kletetschka said.

According to a new study, the polar regions of the Moon may have more than 3,500 cubic kilometers of surface permafrost or subsurface liquid water formed from ions of the Earth’s atmosphere. Researchers have determined its total – 1% of the Earth’s atmosphere reaches the moon.

It is generally believed that majority of the lunar water was deposited by asteroids and comets that collided with the moon. Most were deposited during the period known as the Late Heavy Bombing. It is believed that during this period, about 3.5 billion years ago, when the age of the solar system was about 1 billion years, the early inner planets and the Earth’s Moon were extremely affected by asteroids. Scientists also believe that the source can be the solar wind. The solar wind carries ions of oxygen and hydrogen, which could combine and get to the moon in the form of water molecules.

Now there is an additional way to explain how water accumulates on the moon.

Kletetschka and his colleagues suggest that hydrogen and oxygen ions get to the moon as it passes through the tail of the Earth’s magnetosphere, which it does on five days of the moon’s monthly trip around the planet. The magnetosphere is a teardrop-shaped bubble created by the Earth’s magnetic field that protects the planet from the mostly continuous flow of charged solar particles. Recent measurements by several space agencies – NASA, the European Space Agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the Indian Space Research Organization – have shown that a significant amount of water-forming ions were present during the Moon’s passage through this part of the magnetosphere. These ions have been slowly accumulating since the late heavy bombing.

The presence of the Moon in the tail of the magnetosphere temporarily affects some lines of the Earth’s magnetic field – those that are broken and that simply go into space for many thousands of kilometers. Not all lines of the Earth’s field are attached to the planet at both ends, some have only one point of attachment. Think of each of them as a thread tied to a pole on a windy day.

The presence of the Moon in the magnetic tail causes some of these broken field lines to reconnect with their opposite broken analogs. When this happens, the hydrogen and oxygen ions left by the Earth travel to these newly connected field lines and accelerate back to Earth. The authors of the article suggest that many of these returning ions fall on a passing moon that does not have its own magnetosphere to repel them.

Then the ions combine and form a permafrost. Some of these ions as a result of geological and other processes, such as collisions with asteroids, fall below the surface, where they can turn into liquid water.

The research team used gravitational data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to study polar regions, as well as several large lunar craters. Anomalies in underground areas in impact craters indicate places of rock that may contain liquid water or ice. Gravitational measurements at these subsurface locations indicate the presence of ice or liquid water.

You can also help Ukraine fight with Russian occupants via Savelife or via an official page of the National Bank of Ukraine.

Read also:

- SpaceX Falcon 9 launched the Crew-4 mission to the ISS

- Space presents yet another new phenomenon: ‘Micronova’ explosions on distant zombie stars