© ROOT-NATION.com - Use of content is permitted with a backlink.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, dear readers, but we won’t live forever. Maybe we can hope for a few more decades of breathing, but that’s not enough time to fully grasp and describe the worlds orbiting distant stars.

These mysterious spheres are far too distant in both space and time. Our galaxy is too vast, and the pace of human life is too short compared to the slow rhythm of cosmic time. So, as space enthusiasts, we have to content ourselves with what’s in our own backyard.

If you’re of a certain age, say fifty or younger, you might feel like you’ve missed the golden age of space exploration when humanity first stepped out into this realm. Today’s youth, born just in time to not only see what the surface of the Moon looks like but also to witness people walking on it in real time, are truly fortunate.

A bygone era

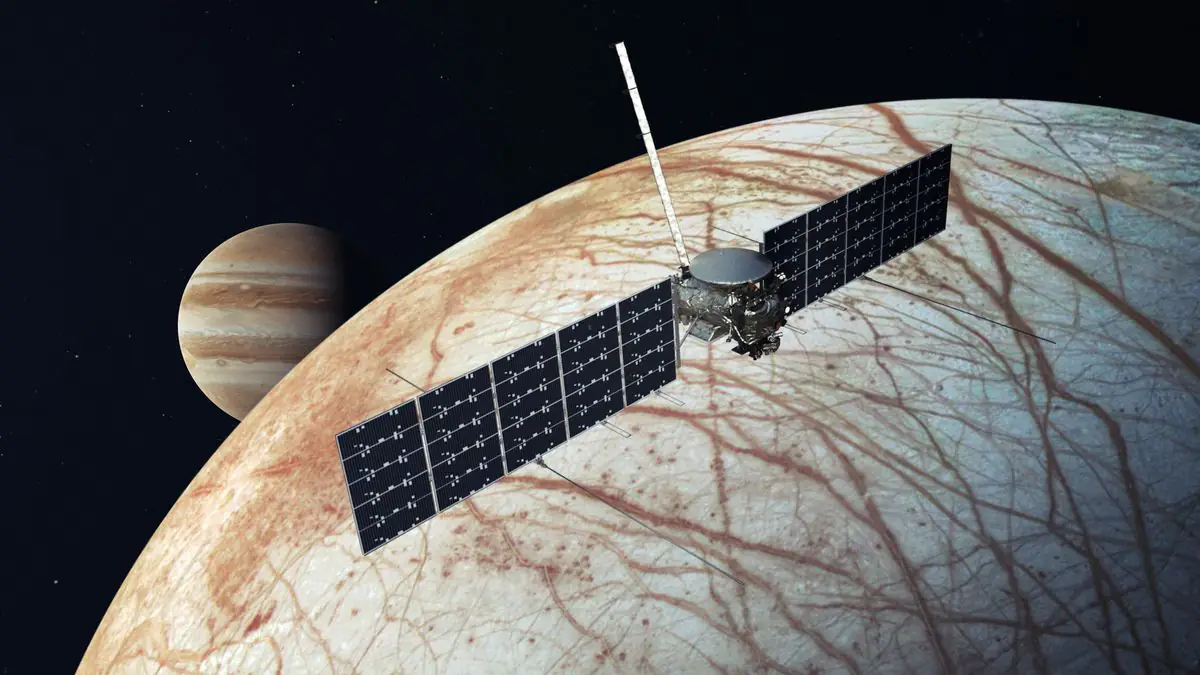

What an era that was! Before that, everything except the Sun and the Moon was just a dot in the night sky. In 1962, Mariner 2 became the first spacecraft to reveal Venus. A few years later, Mariner 4 flew past Mars. Then came the Voyagers, which passed Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1980 and 1981, Uranus in 1986, and Neptune in 1989. And let’s not forget the Viking landers in the mid-1970s, which proved that there were no little green men on Mars.

In the past decade, we have been making constant discoveries. Ten years ago, the European spacecraft Rosetta provided unprecedented images of a comet, and then the tiny lander Philae descended onto its surface and revealed a winter wonderland. The following year, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto and its moon Charon, uncovering numerous wonders, including actual icy volcanoes.

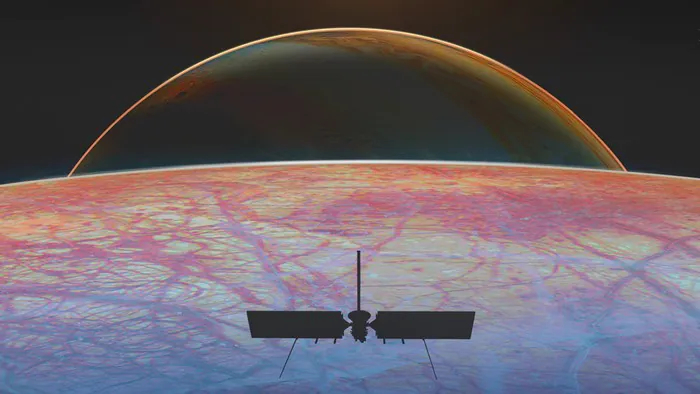

These recent discoveries are just appetizers for the largest unexplored world in our Solar System, a place that hides dark secrets yet to be uncovered. Of course, I’m talking about Europa, Jupiter’s ice-covered moon. Beneath its thick layer of ice lies a vast, warm ocean. Scientists believe that the conditions at the bottom of this immense global sea may be similar to those near hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor of Earth, where life could have originated on our planet. We can only speculate on fundamental questions, such as: How thick is the ice? How deep is the ocean? What secrets lie in its dark depths? Could there truly be marine life there?

The magic of this moment lies in the fact that we are finally setting off. If you’ve ever wanted to witness a true mission of discovery to an unknown yet captivating world, this is the moment.

This weekend, the Falcon Heavy rocket will soar into the sky, carrying the $4.25 billion Europa Clipper spacecraft. This mission may not provide a definitive answer to whether life exists in the oceans below, but it will tell us if it could exist and answer many other questions about the icy moon. The best part is the unknown wonders it will unveil. We can’t even begin to imagine what they might be, but we can be sure that if all goes well, the Clipper will be an exhilarating mission that takes our breath away.

Read also: What Passenger Airplanes of the Future Will Look Like

How did it all start?

After Voyager’s two flybys in 1979, NASA sent a dedicated probe, Galileo, to Jupiter in the 1990s. During its nearly eight years in orbit around Jupiter, this spacecraft made several flybys of Europa, and the data obtained during this mission suggested the likely presence of a watery ocean beneath the moon’s icy surface. In the nearly three decades since then, planetary scientists have had little more than these tantalizing hints. They have been eager to learn more.

Almost immediately after Galileo transmitted its first data about Europa to Earth in 1996, then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin approached scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California with the question of whether a small mission to study Europa was feasible. Adhering to Goldin’s principle of “faster, better, cheaper,” he aimed to develop a spacecraft design that would carry only 27 kg of scientific instruments to Europa.

“This was the beginning of the concept for an orbital satellite around Europa,” said science writer David Brown, author of the book Mission, which tells the definitive story of the Europa Clipper mission.

The initial scientific objectives outlined during the development of this orbital spacecraft—exploring the composition of Europa’s icy shell and ocean, studying the geology of the moon, and finding and characterizing any plumes emanating from the ocean below—have remained largely unchanged for Clipper as well. However, as is often the case with space missions, the budget doubled. NASA’s science director at the turn of the century, astrophysicist Ed Weiler, ultimately scrapped the burgeoning Europa program.

However, scientists remained interested. In 2003, the National Research Council published its first “decadal survey”—a process through which the scientific community outlines research priorities for NASA. Over the years, these decadal surveys have become a significant tool for shaping NASA’s policy. In this first survey, scientists recommended that NASA create a “flagship” mission to study Europa.

At the time, NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe aimed to develop a new generation of spacecraft powered by nuclear reactors under the Prometheus project. He believed that a mission with Europa as its primary target would be an ideal test case for this technology, leading to the conception of an orbital spacecraft for exploring Jupiter’s icy moons. This was a highly ambitious mission. A typical spacecraft consumes only a few hundred watts of power, while this probe, powered by a nuclear reactor, was designed to generate around 100,000 watts.

The Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JIMO) was bold in several aspects, including its plan to utilize a lander component for direct sampling of Europa’s ice. Unfortunately, the mission became exceedingly expensive, with a budget exceeding $20 billion. When Mike Griffin took over as the new administrator in 2005, the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter was ultimately canceled.

Galileo sparked incredible interest in Europa. Initially, NASA attempted a quick and inexpensive mission. Then, the agency worked on the most ambitious spacecraft concept ever proposed. Both attempts ultimately failed, resulting in a lost decade of exploration.

Read also: What passenger trains of the future will look like

New champion

In 2000, conservative Texas attorney John Culberson was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. For a time, he focused on local issues, such as highway construction in the Houston area. However, after the cancellation of the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, he became furious.

Most people in Congress, if they care about NASA at all, do so primarily for their own interests and local jobs. For Culberson, this meant focusing on the Johnson Space Center, located in his neighboring district. However, he was also deeply interested in planetary exploration and wanted to be involved in NASA’s first mission to search for life on another world. As a member of the House Appropriations Committee, Culberson began to allocate funds in NASA’s budget for the exploration of the Europa orbiter.

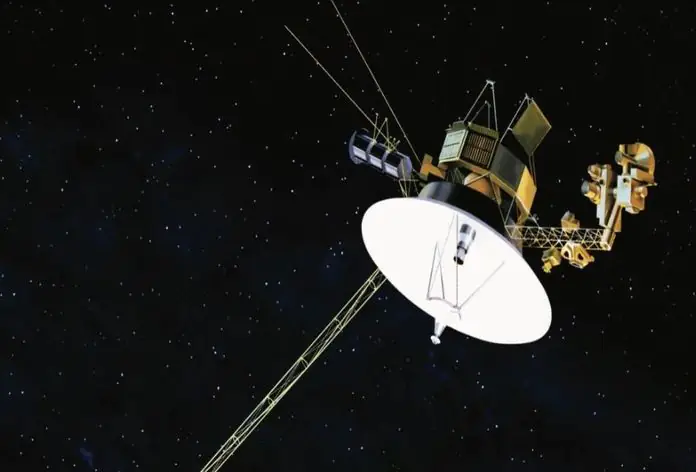

In 2007, NASA began studying mission concepts for Europa and Ganymede in Jupiter’s system, as well as for Titan and Enceladus around Saturn. After working with international partners for two years, NASA ultimately settled on a combined mission, where the U.S. space agency would develop an orbiter for Europa, while the European Space Agency would design one for Ganymede. Eventually, the European mission was launched under the name JUICE in 2023. NASA’s portion of the mission was known as the Jupiter Europa Orbiter.

However, a year later, NASA’s new administrator, Charles Bolden, was looking for ways to cut the agency’s budget. As you might expect, this led to inevitable consequences. The budget for the Jupiter Europa Orbiter soared to over $3 billion. Additionally, there was another issue: Mars had become the focal point of the agency’s research interests.

“For the first time in 20 years, Mars was competing with other planets,” said Brown. “The top priority in the context of a limited budget became the return of samples from Mars. As a result, the Europa Orbiter mission was canceled.” Once again, Calberson was dissatisfied. But this time, he would soon have the opportunity to do something about it.

Read also: Transistors of the Future: New Era of Chips Awaits Us

Looking behind the curtain

In 2012, NASA initiated a new series of studies to redefine the Europa mission. The leading candidate that emerged from this process was a spacecraft capable of making multiple flybys of Jupiter’s moon, known as Europa Clipper. Scientists realized that building an orbital spacecraft was impractical due to its short operational lifespan caused by the constant exposure to the intense radiation emanating from Jupiter. By conducting dozens of flybys, Clipper would be able to enter the inner Jovian system, collect data from Europa, and then transmit it back to Earth when the spacecraft was far enough from Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment.

Starting in the 2013 fiscal year, Calberson began adding funds to NASA’s budget specifically for the development of the Clipper mission, even though NASA had not yet committed to launching the program. “We’ll only have one chance at this in our lifetime,” he said, explaining his efforts to push NASA to green-light the Europa mission after nearly two decades of uncertainty. “We have only one shot. I want to be sure that we’re here to see the first tube worms and lobsters on Europa.”

NASA could not afford to ignore Calberson, who was no longer a junior congressman. In December 2013, Congressman Frank Wolf, a Republican from Virginia, announced he would not seek re-election in 2014, leaving Calberson as the frontrunner to chair the appropriations subcommittee overseeing NASA. In effect, this gave Calberson control over the agency’s budget.

In January 2015, it happened. Now the chair of the crucial budget subcommittee, Calberson began to visit the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California regularly. During these meetings, Calberson, whom everyone called “Mr. Chair,” made suggestions and encouraged scientists to be bold in their design and tool choices. He always asked how much funding they needed and then provided it during the next budget cycle. All of this happened, to varying degrees, because Calberson felt that Clipper was important for the nation.

Eventually, NASA leadership came to terms with the inevitable and made formal commitments to the Clipper mission. According to Brown, many people at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and NASA headquarters in Washington were responsible for developing the Clipper concept and keeping the idea alive. “Without John Culberson, none of this would have happened,” Brown said. “If you want to break it down to dollars and cents, he’s the one who funded this thing and got it to where it needed to fly.”

What will Clipper do?

The launch of Clipper on a fully reusable Falcon Heavy rocket, unfortunately, marks only the end of the beginning of the mission. The spacecraft will take 5.5 years to reach the Jupiter system. During this time, it will cover an incredible distance of 2.9 billion kilometers.

Upon arriving at Jupiter, the spacecraft will complete 80 orbits around the planet, including 49 flybys of Europa. During some of these flybys, the spacecraft will approach the moon’s surface to within 25 kilometers, providing us with an incredible view of the ice and any plumes.

Plumes would indeed be incredibly exciting, as they would provide direct evidence of what lies beneath the surface ocean. There are some fragmentary pieces of evidence from Galileo and observations from the Hubble Space Telescope suggesting that such plumes may be breaking through cracks. However, we just don’t know for sure.

Read also: What is Spatial Audio, How Does It Work, and How to Use It

Technical characteristics

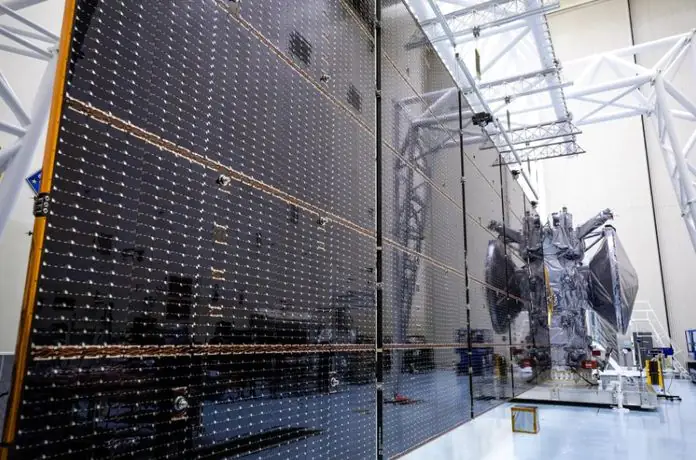

Clipper is the largest spacecraft ever launched by humans into deep space. It ultimately did not receive a nuclear power source, so it is equipped with massive solar panels. The spacecraft carries a complex set of instruments, including a powerful ice-penetrating radar that will study the boundary between the icy crust and the ocean, potentially revealing bodies of water or lakes beneath the surface.

The Europa Clipper spacecraft was built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Its construction cost nearly $5 billion, making it the heaviest automatic interplanetary station in the organization’s history. The Europa Clipper has a mass of 6,025 kg, with 2,750 kg allocated for fuel. It will be powered by two significant solar panels, each composed of five segments, measuring a total length of 14.2 m and a height of 4.1 m. These are the largest solar panels ever equipped on NASA’s interplanetary spacecraft. Once deployed, the width of the Europa Clipper will measure 30.5 m.

The substantial size of the Europa Clipper is due to its orbit around Jupiter, which lies over 700 million kilometers from the Sun. The vicinity of the gas giant receives only about 3% to 4% of the sunlight that reaches Earth. Therefore, engineers had no choice but to install solar panels of such significant dimensions.

The scientific payload of the Europa Clipper consists of nine instruments. Three of these (a mass spectrometer, a dust analyzer, and a spectrograph) will study Europa’s very thin atmosphere, which comprises ice particles and dust ejected into space during impacts from micrometeorites, as well as water vapor likely originating from geysers.

The Europa Clipper will also extensively map Europa using a suite of cameras. A mass spectrometer with imaging capabilities, known as MISE, will help create a map of the distribution of salts and organic molecules on its surface. The spacecraft is equipped with an instrument that will detect thermal emissions, aiding in the search for geyser regions. To peer beneath the moon’s icy shell, Europa Clipper will utilize radar and a magnetometer. The data collected will help determine the thickness and salinity of Europa’s ocean.

In addition to the scientific instruments, the Europa Clipper also carries a metal plate engraved with a symbolic message. The centerpiece of this message is a poem written by poet Ada Limón specifically for the mission. The plate also features various pronunciations of the word “water” in different languages, the Drake Equation, and a portrait of Ron Greeley (1939-2011), who is considered one of the founders of planetology.

Along with the poem, the Europa Clipper will also carry the names of 2.6 million people who participated in NASA’s “Messages in a Bottle” initiative. These names are engraved on a silicon chip the size of a fingernail. This chip is placed on an illustration depicting the orbits of Jupiter’s four largest moons, with a bottle at its center symbolizing NASA’s initiative.

Read also: All about the Rosalind Franklin rover, part of the ExoMars program

Conclusions

Although this is not a mission aimed at discovering life, scientists might get lucky and find signs of life in the plumes or on the surface. However, it is more likely that they will simply describe the moon and its ocean, with the intention of returning in the (distant) future with a lander to conduct ground measurements and potentially discover life.

However, the most exciting aspect is that Clipper is truly venturing into the unknown. This is a mission of pure discovery of one of the most intriguing worlds near Earth. Every time we explore a new place in space, nature always surprises us. “We’ve always discovered things we couldn’t have imagined,” said Bonnie Buratti, the deputy principal investigator for the Clipper project, during a recent briefing. And that really is the case.

Europa holds many secrets, and we are finally pursuing them. If you’re interested in articles and news about aviation and space technology, we invite you to check out our new project, AERONAUT.media.

Read also: